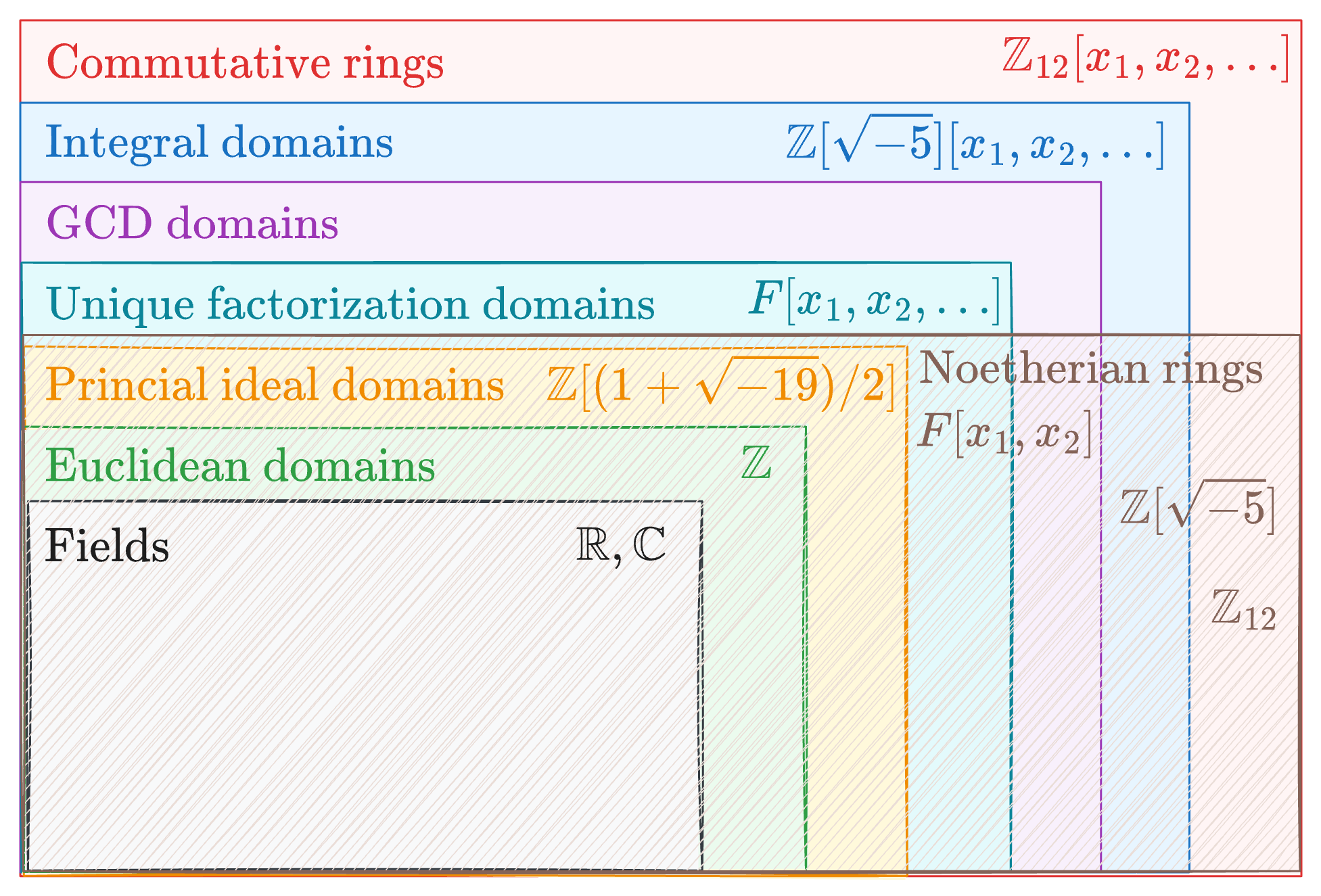

2.4 Rings taxonomy

Rings can have different structures and properties because they use two operations: addition and multiplication. The diagram below shows different kinds of rings and how they fit together. We're going to look at and define a few of these types of rings, that will be useful in our discussions.

Commutative rings

def: Commutative ring

∢ A ∈ R 1 ∀ x , y ∈ A : x ⋅ y = y ⋅ x A ∈ R C ( A is an commutative ring ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&A \in \mathcal R^1 \\

&\forall x, y \in A: x\cdot y = y \cdot x

\\

\hline

\\

&A \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \,\,\, (A \text { is an commutative ring})

\end{align*} ∢ A ∈ R 1 ∀ x , y ∈ A : x ⋅ y = y ⋅ x A ∈ R C ( A is an commutative ring ) Here we assume that commutative ring necessary has an identity. Some textbooks don't assume that and some do.

Example 3: Commutative ring

A ring Z \Z Z

Example 4: Non-commutative ring

A ring of 2x2 matrices over real numbers under matrix + + + ⋅ \cdot ⋅

def: a divides b

∢ A ∈ R C a , b ∈ A , ∃ c ∈ A : b = a c a ∣ b ( a divides b ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&A \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&a, b \in A, \exists c \in A: b = ac\\

\hline

\\

&a \mid b \,\,\,(a\text{ divides } b)

\end{align*} ∢ A ∈ R C a , b ∈ A , ∃ c ∈ A : b = a c a ∣ b ( a divides b ) def: Prime element

∢ A ∈ R C p ∈ A ∖ { 0 } : ( p ∣ a b ⟹ ( p ∣ a ) ∨ ( p ∣ b ) ) r ∈ P ( A ) ( r is a prime in A ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&A \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&p \in A \setminus \{0\}: (p\mid ab \implies (p\mid a) \vee(p\mid b))

\\

\hline

\\

&r \in \mathfrak P(A)\,\,\, (r \text{ is a prime in } A)

\end{align*} ∢ A ∈ R C p ∈ A ∖ { 0 } : ( p ∣ ab ⟹ ( p ∣ a ) ∨ ( p ∣ b )) r ∈ P ( A ) ( r is a prime in A ) Proposition 2.4.1 Prime element and Prime ideal

∢ A ∈ R C p ∈ A p ∈ P ( A ) ⟺ ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ P I ( A ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&A \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&p \in A \\

\hline

\\

&p \in \mathfrak P(A) \iff \lang p \rang_I \in \mathfrak P_I(A)

\end{align*} ∢ A ∈ R C p ∈ A p ∈ P ( A ) ⟺ ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ P I ( A ) Proof

p ∈ P ( A ) ⟺ ( p ∣ a b ⟹ ( p ∣ a ) ∨ ( p ∣ b ) ) ⟺ ( ∃ z ∈ A : a b = p z ⟹ ( ∃ x ∈ A : p = a x ) ∨ ( ∃ y ∈ A : p = b y ) ) ⟺ ( a b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ( a ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) ) p \in \mathfrak P(A) \iff (p \mid ab \implies (p \mid a) \vee (p \mid b) ) \iff \\ (\exists z \in A: ab = pz \implies (\exists x \in A: p=ax) \vee (\exists y \in A: p=by)) \iff \\

(ab \in \lang p \rang_I \implies (a \in \lang p \rang_I)\vee(b \in \lang p \rang_I)) p ∈ P ( A ) ⟺ ( p ∣ ab ⟹ ( p ∣ a ) ∨ ( p ∣ b )) ⟺ ( ∃ z ∈ A : ab = p z ⟹ ( ∃ x ∈ A : p = a x ) ∨ ( ∃ y ∈ A : p = b y )) ⟺ ( ab ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ( a ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I )) □ \square □

∢ R ∈ R C S ⊆ R , S = { a 1 , … , a k } ⟨ S ⟩ I = { r 1 a 1 + … + r k a k , r i ∈ R } \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&S \subseteq R, S = \{a_1, \ldots, a_k\} \\

\hline

\\

&\lang S \rang_I =\{r_1a_1+\ldots+r_ka_k, r_i \in R\}

\end{align*} ∢ R ∈ R C S ⊆ R , S = { a 1 , … , a k } ⟨ S ⟩ I = { r 1 a 1 + … + r k a k , r i ∈ R } Proof

Denote I = { r 1 a 1 + … + r k a k , r i ∈ R } I=\{r_1a_1+\ldots+r_ka_k, r_i \in R\} I = { r 1 a 1 + … + r k a k , r i ∈ R } I ⊆ R R : I \subseteq_R R: I ⊆ R R :

I ≠ ∅ ∀ s 1 , s 2 ∈ I : s 1 − s 2 = r 1 , 1 a 1 + … + r k , 1 a k − r 2 , 1 a 1 − … − r 2 , k a k = = r 3 , 1 a 1 + … + r 3 , k a k ∈ I ∀ r ∈ R , s ∈ I : r s = r r 1 a 1 + … + r r k a k ∈ I I \ne \empty \\

\forall s_1, s_2 \in I: s_1 - s_2 = r_{1,1}a_1+\ldots+r_{k, 1}a_k - r_{2, 1}a_1-\ldots-r_{2, k}a_k = \\

=r_{3, 1}a_1+\ldots+r_{3, k}a_k \in I \\

\forall r \in R, s \in I:rs=rr_1a_1+\ldots+rr_ka_k \in I I = ∅ ∀ s 1 , s 2 ∈ I : s 1 − s 2 = r 1 , 1 a 1 + … + r k , 1 a k − r 2 , 1 a 1 − … − r 2 , k a k = = r 3 , 1 a 1 + … + r 3 , k a k ∈ I ∀ r ∈ R , s ∈ I : rs = r r 1 a 1 + … + r r k a k ∈ I By ( 2.3.3 ) (2.3.3) ( 2.3.3 ) I ⊆ R R I \subseteq_R R I ⊆ R R r I ⊆ I rI \subseteq I r I ⊆ I R ∈ R C R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} R ∈ R C I r ⊆ I I r \subseteq I I r ⊆ I I ⊲ R R I \lhd_R R I ⊲ R R

Finally it's obvious that S ⊆ I S \subseteq I S ⊆ I S S S I I I r i a i r_ia_i r i a i

□ \square □

Integral domains

def: Integral domain

∢ B ∈ R C ∀ x , y ∈ B ∖ { 0 } : x ⋅ y ≠ 0 B ∈ R I D ( B is an integral domain ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&\forall x, y \in B \setminus \{0\}: x\cdot y \ne 0

\\

\hline

\\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} \,\,\, (B \text { is an integral domain})

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R C ∀ x , y ∈ B ∖ { 0 } : x ⋅ y = 0 B ∈ R I D ( B is an integral domain ) Example 5: Integral domain

A ring Z \Z Z Z ∖ { 0 } \Z \setminus \{0\} Z ∖ { 0 } 0 0 0

Example 6: Non-integral domain

Z 6 ∈ R C , Z 6 ∉ R I D \Z_6 \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C}, \Z_6 \notin \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} Z 6 ∈ R C , Z 6 ∈ / R I D 2 ⋅ 3 = 0 ( m o d 6 ) 2 \cdot 3 = 0 \pmod 6 2 ⋅ 3 = 0 ( mod 6 )

Proposition 2.4.3 Cancellation law

∢ B ∈ R I D ∀ a , b , c ∈ B : a b = a c ⟹ ( a = 0 ) ∨ ( b = c ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}}

\\

\hline

\\

&\forall a, b, c\in B: ab=ac \implies (a=0) \vee(b=c)

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D ∀ a , b , c ∈ B : ab = a c ⟹ ( a = 0 ) ∨ ( b = c ) Proof

a b = a c ⟹ a ( b − c ) = 0 ⟹ ( a = 0 ) ∨ ( b − c = 0 ) ab=ac \implies a(b-c)=0 \implies (a=0)\vee(b-c=0) ab = a c ⟹ a ( b − c ) = 0 ⟹ ( a = 0 ) ∨ ( b − c = 0 ) □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.4 Finite integral domain is a field

∢ B ∈ R I D ∣ B ∣ < ∞ ∀ a ∈ B ∖ { 0 } : ∃ b ∈ B : a b = 1 \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} \\

&|B| < \infty

\\

\hline

\\

&\forall a \in B \setminus \{0\}: \exists b \in B: ab = 1

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D ∣ B ∣ < ∞ ∀ a ∈ B ∖ { 0 } : ∃ b ∈ B : ab = 1 Proof

∀ a ∈ B ∖ { 0 } , f : B → B , x ↦ a x ⟹ ( 2.4.3 ) f : B → 1 − 1 B ⟹ ∣ B ∣ = ∣ f ( B ) ∣ ⟹ f ( B ) ⊆ B B = f ( B ) ⟹ f : B ↔ B ⟹ ∃ b ∈ B : a b = 1 \forall a \in B \setminus \{0\}, f: B \to B, x \mapsto ax \overset{(2.4.3)}{\implies} f: B\overset{1-1}{\to} B \implies \\

|B|=|f(B)| \overset{f(B) \subseteq B}{\implies}\\

B = f(B) \implies f: B \leftrightarrow B \implies \exists b \in B: ab = 1 ∀ a ∈ B ∖ { 0 } , f : B → B , x ↦ a x ⟹ ( 2.4.3 ) f : B → 1 − 1 B ⟹ ∣ B ∣ = ∣ f ( B ) ∣ ⟹ f ( B ) ⊆ B B = f ( B ) ⟹ f : B ↔ B ⟹ ∃ b ∈ B : ab = 1 □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.5 Characteristic is prime or 0

∢ B ∈ R I D ( char B = 0 ) ∨ ( char B ∈ P ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal ID}

\\

\hline

\\

&(\text{char }B=0)\vee(\text{char }B \in \mathfrak P)

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D ( char B = 0 ) ∨ ( char B ∈ P ) Proof

char B > 0 , char B ∉ P ⟹ char B = n = a b , 1 < a , b < n ⟹ 0 = n ⋅ 1 = ( a ⋅ 1 ) ( b ⋅ 1 ) ⟹ B ∈ R I D ( a ⋅ 1 = 0 ) ∨ ( b ⋅ 1 = 0 ) ⟹ ( 2.3.2 ) char B < n \text{char } B > 0, \text{char } B \notin \mathfrak P \implies \\

\text{char } B = n = ab, 1 < a, b < n \implies \\

0=n\cdot1 = (a\cdot 1)(b\cdot 1) \overset{B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal ID}}\implies \\(a\cdot 1 = 0) \vee (b\cdot 1 = 0) \overset{(2.3.2)}\implies \text{char } B < n char B > 0 , char B ∈ / P ⟹ char B = n = ab , 1 < a , b < n ⟹ 0 = n ⋅ 1 = ( a ⋅ 1 ) ( b ⋅ 1 ) ⟹ B ∈ R I D ( a ⋅ 1 = 0 ) ∨ ( b ⋅ 1 = 0 ) ⟹ ( 2.3.2 ) char B < n Thus, ( char B = 0 ) ∨ ( char B ∈ P ) (\text{char }B=0)\vee(\text{char }B \in \mathfrak P) ( char B = 0 ) ∨ ( char B ∈ P )

□ \square □

def: Unit

∢ R ∈ R 1 u ∈ R : ∃ v ∈ R : u ⋅ v = v ⋅ u = 1 u ∈ R ∗ ( u is a unit ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&R \in \mathcal R^1 \\

&u \in R: \exists v \in R: u \cdot v=v \cdot u=1

\\

\hline

\\

&u \in R^* \,\,\,(u\text{ is a unit})

\end{align*} ∢ R ∈ R 1 u ∈ R : ∃ v ∈ R : u ⋅ v = v ⋅ u = 1 u ∈ R ��∗ ( u is a unit ) def: Irreducible element

∢ B ∈ R I D r ∈ B ∖ ( B ∗ ∪ { 0 } ) , ( r = u v ⟹ ( u ∈ B ∗ ) ∨ ( v ∈ B ∗ ) ) r ∈ B − ( r is an irreducible element of B ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

&r \in B \setminus (B^* \cup \{0\}), (r = uv \implies (u \in B^*) \vee(v \in B^*))

\\

\hline

\\

&r \in B^{-} \,\,\, (r \text{ is an irreducible element of } B)

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D r ∈ B ∖ ( B ∗ ∪ { 0 }) , ( r = uv ⟹ ( u ∈ B ∗ ) ∨ ( v ∈ B ∗ )) r ∈ B − ( r is an irreducible element of B ) def: Reducible element

∢ B ∈ R I D r , s , t ∈ B ∖ ( B ∗ ∪ { 0 } ) : r = s t r ∈ B + − reducible \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

&r, s, t \in B \setminus (B^* \cup \{0\}): r = st

\\

\hline

\\

&r \in B^+ - \text{reducible}

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D r , s , t ∈ B ∖ ( B ∗ ∪ { 0 }) : r = s t r ∈ B + − reducible Any element of integral domain is either 0, unit, reducible or irreducible. Thus B = { 0 } ∪ B ∗ ∪ B + ∪ B − B = \{0\} \cup B^* \cup B^+ \cup B^- B = { 0 } ∪ B ∗ ∪ B + ∪ B −

In theory we could define units, reducible and irreducible elements for commutative rings, however in this case we won't have this neat property as commutative ring can have zero divisors.

The other way to think about reducible and irreducible is as follows: consider a subset of non-zero, non-invertible elements of B B B

Proposition 2.4.6 Units, divisibility and ideals

∢ B ∈ R I D a , b ∈ B ∖ { 0 } I ⊲ R B a ∣ b ⟺ ⟨ b ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ∃ u ∈ B ∗ : b = a u ⟺ ⟨ a ⟩ I = ⟨ b ⟩ I B ∗ ∩ I ≠ ∅ ⟺ I = B \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} \\

&a, b \in B \setminus \{0\} \\

&I \lhd_R B

\\

\hline

\\

&\begin{align*}

& a \mid b \iff \lang b \rang_I \subseteq \lang a \rang_I \tag{a}\\

& \exists u \in B^*: b = au \iff \lang a \rang_I = \lang b \rang_I \hspace{1cm} \tag{b}\\

& B^* \cap I \ne \empty \iff I = B \tag{c}\\

\end{align*}

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D a , b ∈ B ∖ { 0 } I ⊲ R B a ∣ b ⟺ ⟨ b ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ∃ u ∈ B ∗ : b = a u ⟺ ⟨ a ⟩ I = ⟨ b ⟩ I B ∗ ∩ I = ∅ ⟺ I = B ( a ) ( b ) ( c ) Proof

a.

⟹ \implies ⟹

a ∣ b ⟹ ∃ c ∈ B : b = a c ⟹ ∀ x ∈ ⟨ b ⟩ I : ∃ r ∈ B : x = r b = r a c = r c a ∈ ⟨ a ⟩ I a \mid b \implies \exists c \in B: b = ac \implies \\\forall x \in \lang b \rang_I: \exists r \in B: x = rb=rac=rca \in \lang a \rang_I \\ a ∣ b ⟹ ∃ c ∈ B : b = a c ⟹ ∀ x ∈ ⟨ b ⟩ I : ∃ r ∈ B : x = r b = r a c = rc a ∈ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

⟨ b ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ b ∈ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ r ∈ B : b = r a ⟹ a ∣ b \lang b \rang_I \subseteq \lang a \rang_I \implies b \in \lang a \rang_I \implies \exists r \in B: b = ra \implies a \mid b ⟨ b ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ b ∈ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ r ∈ B : b = r a ⟹ a ∣ b b.

⟹ \implies ⟹

∃ u ∈ B ∗ : b = a u ⟹ ( a ) ⟨ b ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I a = b u − 1 ⟹ ( a ) ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ b ⟩ I \exists u \in B^*: b = au \overset{(a)}\implies \lang b \rang_I \subseteq \lang a \rang_I \\

a = bu^{-1} \overset{(a)}{\implies} \lang a \rang_I \subseteq \lang b \rang_I ∃ u ∈ B ∗ : b = a u ⟹ ( a ) ⟨ b ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I a = b u − 1 ⟹ ( a ) ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ b ⟩ I ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

⟨ b ⟩ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ ( a ) a ∣ b , b ∣ a ⟹ ∃ x , y ∈ B : a = b x , b = a y = b x y ⟹ x y = 1 ⟹ ∃ u = y ∈ B ∗ , b = a u \lang b \rang_I = \lang a \rang_I \overset{(a)}{\implies} a \mid b, b \mid a \implies \exists x, y \in B: a = bx, b = ay = bxy \implies \\ xy=1 \implies \exists u=y \in B^*, b = au ⟨ b ⟩ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ ( a ) a ∣ b , b ∣ a ⟹ ∃ x , y ∈ B : a = b x , b = a y = b x y ⟹ x y = 1 ⟹ ∃ u = y ∈ B ∗ , b = a u c.

⟹ \implies ⟹

a ∈ B ∗ ∩ I ⟹ a a − 1 ∈ I ⟹ 1 ∈ I ⟹ ∀ r ∈ R : r = r ⋅ 1 ⊆ I ⟹ R = I a \in B^* \cap I \implies aa^{-1} \in I \implies 1 \in I \implies \\

\forall r \in R: r = r\cdot 1 \subseteq I \implies R = I a ∈ B ∗ ∩ I ⟹ a a − 1 ∈ I ⟹ 1 ∈ I ⟹ ∀ r ∈ R : r = r ⋅ 1 ⊆ I ⟹ R = I ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

R = I ⟹ 1 ∈ B ∗ ∩ I ⟹ B ∗ ∩ I ≠ ∅ R = I \implies 1 \in B^* \cap I \implies B^* \cap I \ne \empty R = I ⟹ 1 ∈ B ∗ ∩ I ⟹ B ∗ ∩ I = ∅ □ \square □

The ( d ) (d) ( d )

Proposition 2.4.7 Prime is irreducible

∢ B ∈ R I D p ∈ P ( B ) p ∈ B − \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

&p \in \mathfrak P(B)

\\

\hline

\\

&p \in B^-

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D p ∈ P ( B ) p ∈ B − Proof

p ∈ P ( B ) ⟹ ( 2.4.1 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ P I ( B ) p = a b ⟹ a b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ( a ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) { a ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ r ∈ B : p = a b = p r b ⟹ ( 2.4.3 ) r b = 1 ⟹ b ∈ B ∗ b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ r ∈ B : p = a b = a r p ⟹ ( 2.4.3 ) a r = 1 ⟹ a ∈ B ∗ p \in \mathfrak P(B) \overset{(2.4.1)}{\implies} \lang p \rang_I \in \mathfrak P_I(B) \\

p = ab \implies ab \in \lang p \rang_I \implies (a \in \lang p \rang_I) \vee (b \in\lang p \rang_I) \\

\begin{cases}

a \in \lang p \rang_I \implies \exists r \in B:p = ab=prb \overset{(2.4.3)}{\implies} rb = 1 \implies b \in B^* \\

b \in \lang p \rang_I \implies \exists r \in B:p = ab=arp \overset{(2.4.3)}{\implies} ar = 1 \implies a \in B^*

\end{cases} p ∈ P ( B ) ⟹ ( 2.4.1 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ P I ( B ) p = ab ⟹ ab ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I �� ⟹ ( a ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ) ⎩ ⎨ ⎧ a ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ r ∈ B : p = ab = p r b ⟹ ( 2.4.3 ) r b = 1 ⟹ b ∈ B ∗ b ∈ ⟨ p ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ r ∈ B : p = ab = a r p ⟹ ( 2.4.3 ) a r = 1 ⟹ a ∈ B ∗ □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.8 Factor ring by prime ideal is an integral domain

∢ R ∈ R C I ⊲ R R I ∈ P I ⟺ R / I ∈ R I D \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&I \lhd_R R \\

\hline

\\

&I \in \mathfrak P_I \iff R/I \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}}

\end{align*} ∢ R ∈ R C I ⊲ R R I ∈ P I ⟺ R / I ∈ R I D Proof

⟹ \implies ⟹

∀ a + I , b + I ∈ R / I : ( a + I ) ( b + I ) = I ⟹ a b + I = I ⟹ a b ∈ I ⟹ I ∈ P I ( a ∈ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ I ) ⟹ ( a + I = I ) ∨ ( b + I = I ) \forall a + I, b + I \in R/I: (a+I)(b+I)=I \implies ab+I=I \implies \\

ab \in I \overset{I \in \mathfrak P_I}{\implies} (a \in I) \vee (b \in I) \implies (a+I = I) \vee(b+I = I) ∀ a + I , b + I ∈ R / I : ( a + I ) ( b + I ) = I ⟹ ab + I = I ⟹ ab ∈ I ⟹ I ∈ P I ( a ∈ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ I ) ⟹ ( a + I = I ) ∨ ( b + I = I ) ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

∀ a , b ∈ R : a b ∈ I ⟹ I = a b + I = ( a + I ) ( b + I ) ⟹ R / I ∈ R I D ( a + I = I ) ∨ ( b + I = I ) ⟹ ( a ∈ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ I ) \forall a, b \in R:ab \in I \implies I= ab+I = (a+I)(b+I) \overset{ R/I \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}}}{\implies} \\ (a+I=I)\vee(b+I=I) \implies (a \in I)\vee(b \in I) ∀ a , b ∈ R : ab ∈ I ⟹ I = ab + I = ( a + I ) ( b + I ) ⟹ R / I ∈ R I D ( a + I = I ) ∨ ( b + I = I ) ⟹ ( a ∈ I ) ∨ ( b ∈ I ) □ \square □

Noetherian rings

def: Noetherian ring

∢ N ∈ R C ∀ J i ⊲ I N : J 1 ⊆ J 2 ⊆ … : ∃ n 0 : ∀ n ≥ n 0 : J n = J n 0 N ∈ R N ( R is a noetherian ring ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&N \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {C}} \\

&\forall J_i \lhd_I N: J_1 \subseteq J_2 \subseteq \ldots: \exists n_0: \forall n \ge n_0: J_n=J_{n_0}

\\

\hline

\\

&N \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {N}} \,\,\, (R \text{ is a noetherian ring})

\end{align*} ∢ N ∈ R C ∀ J i ⊲ I N : J 1 ⊆ J 2 ⊆ … : ∃ n 0 : ∀ n ≥ n 0 : J n = J n 0 N ∈ R N ( R is a noetherian ring ) Proposition 2.4.9 Ideals are finitely generated

N ∈ R N ⟺ ∀ I ⊲ I N : ∃ S ⊆ N , ∣ S ∣ < ∞ : I = ⟨ S ⟩ I N \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {N}} \iff \forall I \lhd_I N: \exists S \subseteq N, |S| < \infty: I = \lang S \rang_I N ∈ R N ⟺ ∀ I ⊲ I N : ∃ S ⊆ N , ∣ S ∣ < ∞ : I = ⟨ S ⟩ I

Proof

⟹ \implies ⟹

Consider I ⊲ R N I \lhd_R N I ⊲ R N X : = { J ⊲ R I , J = ⟨ j 1 , … , j k ⟩ R } X:= \{J \lhd_R I, J=\lang j_1, \ldots, j_k\rang_R\} X := { J ⊲ R I , J = ⟨ j 1 , … , j k ⟩ R } I I I I ∈ X I \in X I ∈ X

Obviously, X ≠ ∅ X \ne \empty X = ∅

Assume ∀ J ∈ X : ∃ K ∈ X : K ⊃ J \forall J \in X: \exists K \in X: K \supset J ∀ J ∈ X : ∃ K ∈ X : K ⊃ J J 1 J_1 J 1 J 2 : = K ⊃ J 1 J_2:=K \supset J_1 J 2 := K ⊃ J 1 J 3 : = K ⊃ J 2 J_3:=K \supset J_2 J 3 := K ⊃ J 2 J 1 ⊂ J 2 ⊂ J 3 ⊂ … J_1 \subset J_2 \subset J_3 \subset \ldots J 1 ⊂ J 2 ⊂ J 3 ⊂ … N ∈ R N N \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {N}} N ∈ R N

∃ J ∈ X : ∀ K ∈ X : K ⊆ J \exists J \in X: \forall K \in X: K \subseteq J ∃ J ∈ X : ∀ K ∈ X : K ⊆ J Assume J ≠ I J \ne I J = I J ∈ X J \in X J ∈ X X X X J ⊆ I J \subseteq I J ⊆ I J ⊂ I J \subset I J ⊂ I ∃ a ∈ I ∖ J \exists a \in I \setminus J ∃ a ∈ I ∖ J L : = ⟨ a ⟩ I + J L:=\lang a \rang_I+J L := ⟨ a ⟩ I + J L L L L ⊆ I L \subseteq I L ⊆ I L ∈ X L \in X L ∈ X L ⊃ J L \supset J L ⊃ J J J J J = I J=I J = I I I I

⟸ \impliedby ⟸

Consider J 1 ⊆ J 2 ⊆ … J_1 \subseteq J_2 \subseteq \ldots J 1 ⊆ J 2 ⊆ … J : = ∪ i J i J:=\cup_iJ_i J := ∪ i J i J J J

J ≠ ∅ a , b ∈ J ⟹ a ∈ J i , b ∈ J k ⟹ ( ( a − b ) ∈ J i ) ∨ ( ( a − b ) ∈ J k ) ⟹ a − b ∈ J r ∈ N , a ∈ J ⟹ a ∈ J i , r a ∈ J i ⟹ r a ∈ J . J \ne \empty \\

a, b \in J \implies a \in J_i, b \in J_k \implies \\ ((a - b) \in J_i)\vee((a - b) \in J_k) \implies a-b \in J \\

r \in N, a \in J \implies a \in J_i, ra \in J_i \implies ra \in J. J = ∅ a , b ∈ J ⟹ a ∈ J i , b ∈ J k ⟹ (( a − b ) ∈ J i ) ∨ (( a − b ) ∈ J k ) ⟹ a − b ∈ J r ∈ N , a ∈ J ⟹ a ∈ J i , r a ∈ J i ⟹ r a ∈ J . Since by our assumption every ideal is finitely generated, J = ⟨ a 1 , … , a k ⟩ I J=\lang a_1, \ldots, a_k\rang_I J = ⟨ a 1 , … , a k ⟩ I a i ∈ J n i a_i \in J_{n_i} a i ∈ J n i n : = max 1 ≤ i ≤ k n i n:=\max_{1\le i \le k}n_i n := max 1 ≤ i ≤ k n i ∀ i : 1 ≤ i ≤ k : a i ∈ J n \forall i: 1 \le i \le k: a_i \in J_n ∀ i : 1 ≤ i ≤ k : a i ∈ J n J n ⊇ J J_n\supseteq J J n ⊇ J ∀ k ≥ n : J ⊆ J n ⊆ J k ⊆ J \forall k \ge n: J\subseteq J_n \subseteq J_k \subseteq J ∀ k ≥ n : J ⊆ J n ⊆ J k ⊆ J J k = J n J_k=J_n J k = J n

□ \square □

GCD domain

def: Greatest common divisor

∢ R ∈ R I D a , b , d ∈ R d ∈ R : d ∣ a , d ∣ b ∀ d 1 ∈ R : d 1 ∣ a , d 1 ∣ b ⟹ d ∣ d 1 gcd ( a , b ) : = d \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

&a, b, d \in R \\

&d \in R: d \mid a, d \mid b \\

&\forall d_1 \in R: d_1\mid a, d_1\mid b \implies d\mid d_1 \\

\hline

\\

&\gcd(a,b):=d

\end{align*} ∢ R ∈ R I D a , b , d ∈ R d ∈ R : d ∣ a , d ∣ b ∀ d 1 ∈ R : d 1 ∣ a , d 1 ∣ b ⟹ d ∣ d 1 g cd( a , b ) := d def: GCD domain

∢ D ∈ R I D ∀ a , b ∈ D : ∃ gcd ( a , b ) D ∈ R G C D \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&D \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

&\forall a, b \in D: \exists \gcd(a, b)\\

\hline

\\

&D \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {GCD}}

\end{align*} ∢ D ∈ R I D ∀ a , b ∈ D : ∃ g cd( a , b ) D ∈ R G C D Proposition 2.4.10: Divisibility is specified up to a unit

∢ A ∈ R C a , b ∈ R u ∈ R ∗ a ∣ b ⟺ u a ∣ b ⟺ a ∣ u b ⟺ u a ∣ u b \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&A \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

& a, b \in R \\

& u \in R^* \\

\hline

\\

&a \mid b \iff ua \mid b \iff a \mid ub \iff ua\mid ub

\end{align*} ∢ A ∈ R C a , b ∈ R u ∈ R ∗ a ∣ b ⟺ u a ∣ b ⟺ a ∣ u b ⟺ u a ∣ u b Proof

a ∣ b ⟹ b = c a = ( c u − 1 ) u a ⟹ u a ∣ b u a ∣ b ⟹ b = c u a ⟹ u b = ( u c u ) a ⟹ a ∣ u b a ∣ u b ⟹ u b = c a = ( c u − 1 ) u a ⟹ u a ∣ u b u a ∣ u b ⟹ u b = c u a ⟹ b = ( u − 1 c u ) a ⟹ a ∣ b a\mid b \implies b = ca=(cu^{-1})ua \implies ua \mid b \\

ua\mid b \implies b=cua \implies ub=(ucu)a \implies a \mid ub \\

a\mid ub \implies ub=ca=(cu^{-1})ua \implies ua \mid ub \\

ua \mid ub \implies ub = cua \implies b = (u^{-1}cu)a \implies a \mid b a ∣ b ⟹ b = c a = ( c u − 1 ) u a ⟹ u a ∣ b u a ∣ b ⟹ b = c u a ⟹ u b = ( u c u ) a ⟹ a ∣ u b a ∣ u b ⟹ u b = c a = ( c u − 1 ) u a ⟹ u a ∣ u b u a ∣ u b ⟹ u b = c u a ⟹ b = ( u − 1 c u ) a ⟹ a ∣ b □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.11: GCD is unique up to a unit multiple

∢ D ∈ R G C D a , b , d 1 , d 2 ∈ D d 1 ≠ d 2 d 1 = gcd ( a , b ) d 2 = gcd ( a , b ) ∃ u ∈ D ∗ : d 1 = u d 2 \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&D \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {GCD}} \\

&a, b, d_1, d_2 \in D \\

&d_1 \ne d_2 \\

&d_1 = \gcd(a, b) \\

&d_2 = \gcd(a, b)

\\

\hline

\\

&\exists u \in D^*: d_1 = ud_2

\end{align*} ∢ D ∈ R G C D a , b , d 1 , d 2 ∈ D d 1 = d 2 d 1 = g cd( a , b ) d 2 = g cd( a , b ) ∃ u ∈ D ∗ : d 1 = u d 2 Proof

d 1 ∣ d 2 ⟹ ∃ x ∈ D : d 2 = x d 1 d 2 ∣ d 1 ⟹ ∃ u ∈ D : d 1 = u d 2 d 1 = u d 2 = u x d 1 ⟹ 1 = u x ⟹ u ∈ D ∗ d_1 \mid d_2 \implies \exists x \in D: d_2 = xd_1 \\

d_2 \mid d_1 \implies \exists u \in D: d_1 = ud_2 \\

d_1 = ud_2=uxd_1 \implies 1 = ux \implies u \in D^* d 1 ∣ d 2 ⟹ ∃ x ∈ D : d 2 = x d 1 d 2 ∣ d 1 ⟹ ∃ u ∈ D : d 1 = u d 2 d 1 = u d 2 = ux d 1 ⟹ 1 = ux ⟹ u ∈ D ∗ □ \square □

Example: GCD Domain

An example of a GCD domain is the ring of integers Z \Z Z Z \Z Z

Example: Non-GCD Domain

Z [ − 5 ] \Z[\sqrt{-5}] Z [ − 5 ] Z \Z Z − 5 \sqrt{-5} − 5 here .

Unique factorization domains

def: Unique factorization domain

∢ U ∈ R I D 1. ∀ x ∈ ( U ∖ ( U ∗ ∪ { 0 } ) ) : ∃ a 1 , … , a n ∈ U − : x = a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k 2. ∀ a 1 , … , a k , b 1 , … , b n ∈ U − : a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k = b 1 ⋅ … ⋅ b n ⟹ n = k , ∃ σ ∈ S n , u 1 , … , u n ∈ U ∗ : σ ( a i ) = u i b i U ∈ R U F D ( U − unique factorization domain ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&U \in R^{\mathcal{ID}} \\

1.\,\,\, &\forall x \in (U \setminus (U^* \cup \{0\}) ): \exists a_1,\ldots,a_n \in U^{-}:x= a_1 \cdot\ldots \cdot a_k \\

2.\,\,\, & \forall a_1,\ldots,a_k,b_1,\ldots,b_n \in U^- : a_1 \cdot\ldots \cdot a_k=b_1 \cdot\ldots \cdot b_n \implies \\

&n=k, \exists \sigma \in S_n, u_1, \ldots, u_n \in U^*: \sigma(a_i) = u_ib_i

\\

\hline

\\

&U \in \mathcal{R}^{\mathcal{UFD}} \,\,\,(U - \text{unique factorization domain} )

\end{align*} 1. 2. ∢ U ∈ R I D ∀ x ∈ ( U ∖ ( U ∗ ∪ { 0 })) : ∃ a 1 , … , a n ∈ U − : x = a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ∀ a 1 , … , a k , b 1 , … , b n ∈ U − : a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k = b 1 ⋅ … ⋅ b n ⟹ n = k , ∃ σ ∈ S n , u 1 , … , u n ∈ U ∗ : σ ( a i ) = u i b i U ∈ R U F D ( U − unique factorization domain ) A Unique Factorization Domain is basically a type of ring where the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic applies. This theorem states that every element in the ring can be broken down into a product of prime elements, and this breakdown is unique except for the order of the factors. In this context, 'prime' elements are referred to as irreducible elements. This is similar to the definition of prime numbers for integers, with the understanding that in the case of integers, the only units (elements that have a multiplicative inverse) are 1 and -1.

Example 7. Unique factorization domain

Z \Z Z

Example 8. Non-unique factorization domain

Z [ − 5 ] : = { a + b − 5 , a , b ∈ Z } \Z[\sqrt{-5}]:=\{a+b \sqrt{-5}, a, b \in \Z\} Z [ − 5 ] := { a + b − 5 , a , b ∈ Z } 6 = 2 ⋅ 3 = ( 1 − − 5 ) ⋅ ( 1 + − 5 ) 6=2 \cdot 3=(1-\sqrt{-5})\cdot(1+\sqrt{-5}) 6 = 2 ⋅ 3 = ( 1 − − 5 ) ⋅ ( 1 + − 5 )

Proposition 2.4.12: Irreducible = prime

∢ P ∈ R U F D p ∈ P − ⟺ p ∈ P ( A ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{UFD}}

\\

\hline

\\

&p \in P^{-} \iff &p \in \mathfrak P(A)

\end{align*} ∢ P ∈ R U F D p ∈ P − ⟺ p ∈ P ( A ) Proof

⟹ \implies ⟹

Consider a , b ∈ P : p ∣ a b a, b \in P: p \mid ab a , b ∈ P : p ∣ ab P ∈ R U F D P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{UFD}} P ∈ R U F D a = a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ⋅ , b = b 1 ⋅ … ⋅ b n , a i , b i ∈ P − a= a_{1}\cdot \ldots \cdot a_{k}\cdot, b= b_{1}\cdot \ldots \cdot b_{n}, a_i, b_i \in P^- a = a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ⋅ , b = b 1 ⋅ … ⋅ b n , a i , b i ∈ P −

p ∣ a b ⟹ a b = p r ⟹ a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ⋅ b 1 ⋅ … ⋅ b n = p r p \mid ab \implies ab = pr \implies a_{1}\cdot \ldots \cdot a_{k}\cdot b_{1}\cdot \ldots \cdot b_{n} = pr p ∣ ab ⟹ ab = p r ⟹ a 1 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ⋅ b 1 ⋅ … ⋅ b n = p r Note that on the left-hand side we have irreducibles and on the right-hand side p p p r r r p p p

( u p = a i ) ∨ ( v p = b j ) , u , v ∈ P ∗ (up=a_i) \vee (vp=b_j), u, v \in P^* ( u p = a i ) ∨ ( v p = b j ) , u , v ∈ P ∗ If u p = a 1 up=a_1 u p = a 1 p = a 1 u − 1 p = a_1u^{-1} p = a 1 u − 1 a = u − 1 ⋅ p ⋅ a 2 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ⟹ p ∣ a a = u^{-1}\cdot p\cdot a_2 \cdot \ldots \cdot a_k \implies p \mid a a = u − 1 ⋅ p ⋅ a 2 ⋅ … ⋅ a k ⟹ p ∣ a u p = a j ⟹ p ∣ a up=a_j \implies p \mid a u p = a j ⟹ p ∣ a v p = b j ⟹ p ∣ b vp=b_j \implies p \mid b v p = b j ⟹ p ∣ b

⟸ \impliedby ⟸

Follows from ( 2.4.7 ) (2.4.7) ( 2.4.7 )

□ \square □

Proposition 2.4.13: UFD is a GCD domain

∢ U ∈ R U F D U ∈ R G C D \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&U \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {UFD}}

\\

\hline

\\

&U \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {GCD}}

\end{align*} ∢ U ∈ R U F D U ∈ R G C D Proof

Take a , b ∈ U a, b \in U a , b ∈ U a = u p 1 e 1 … p n e n , b = u p 1 f 1 … p n f n , p i ∈ U − , e i , f i ≥ 0 a = up_1^{e_1}\ldots p_n^{e_n}, b = up_1^{f_1}\ldots p_n^{f_n}, p_i \in U^-, e_i, f_i \ge 0 a = u p 1 e 1 … p n e n , b = u p 1 f 1 … p n f n , p i ∈ U − , e i , f i ≥ 0

Define d : = p 1 min ( e 1 , f 1 ) … p n min ( e n , f n ) d:=p_1^{\min(e_1, f_1)}\ldots p_n^{\min(e_n, f_n)} d := p 1 m i n ( e 1 , f 1 ) … p n m i n ( e n , f n ) d ∣ a , d ∣ b d \mid a, d \mid b d ∣ a , d ∣ b

Consider c : c ∣ a , c ∣ b , c = q 1 g 1 … q k g k , q i ∈ U − c: c \mid a, c \mid b, c = q_1^{g_1}\ldots q_k^{g_k}, q_i \in U^- c : c ∣ a , c ∣ b , c = q 1 g 1 … q k g k , q i ∈ U −

q i ∣ c , c ∣ a , c ∣ b ⟹ q i ∣ a , q i ∣ b ⟹ p i , q i ∈ P ∃ j : q i = p j ⟹ { q 1 , … , q k } ⊆ { p 1 , … , p n } c ∣ a , c ∣ b ⟹ g i ≤ min ( e i , f i ) ⟹ d ∣ c q_i \mid c, c \mid a, c \mid b \implies q_i \mid a, q_i \mid b \overset{p_i, q_i \in \mathfrak P}{\implies} \exists j: q_i = p_j \implies \\ \{q_1, \ldots, q_k\} \subseteq \{p_1, \ldots, p_n\} \\

c \mid a, c \mid b \implies g_i \le \min(e_i, f_i) \implies d \mid c q i ∣ c , c ∣ a , c ∣ b ⟹ q i ∣ a , q i ∣ b ⟹ p i , q i ∈ P ∃ j : q i = p j ⟹ { q 1 , … , q k } ⊆ { p 1 , … , p n } c ∣ a , c ∣ b ⟹ g i ≤ min ( e i , f i ) ⟹ d ∣ c □ \square □

Principal ideal domains

def: Principal ideal domains

∢ R ∈ R I D ∀ I ⊲ R R : ∃ a ∈ R : I = ⟨ a ⟩ I R ∈ R P I D ( R − principal ideal domain ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} \\

&\forall I \lhd_R R: \exists a \in R: I=\lang a \rang_I

\\

\hline

\\

&R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {PID}} \,\,\, (R - \text{principal ideal domain})

\end{align*} ∢ R ∈ R I D ∀ I ⊲ R R : ∃ a ∈ R : I = ⟨ a ⟩ I R ∈ R P I D ( R − principal ideal domain ) Example: Principal ideal domain

Z \Z Z Z \Z Z

Example: Non-principal ideal domain

Z [ x ] \Z[x] Z [ x ] I = ⟨ 5 , x ⟩ I I = \lang 5, x \rang_I I = ⟨ 5 , x ⟩ I ∃ p ∈ Z [ x ] : I = ⟨ p ⟩ I \exists p \in \Z[x]: I =\lang p \rang_I ∃ p ∈ Z [ x ] : I = ⟨ p ⟩ I 5 = p ( x ) f ( x ) ⟹ p ( x ) = p ∈ Z 5=p(x)f(x) \implies p(x) = p \in \Z 5 = p ( x ) f ( x ) ⟹ p ( x ) = p ∈ Z x = p g ( x ) ⟹ g ( x ) = ± x , p = ∓ 1 ⟹ ⟨ p ( x ) ⟩ I = Z [ x ] x = pg(x) \implies g(x) = \pm x, p = \mp 1 \implies \lang p(x) \rang_I=\Z[x] x = p g ( x ) ⟹ g ( x ) = ± x , p = ∓ 1 ⟹ ⟨ p ( x ) ⟩ I = Z [ x ] 3 = 5 f ( x ) + x g ( x ) ⟹ g ( x ) = 0 , 3 = 5 f ( x ) 3 = 5f(x)+xg(x) \implies g(x) = 0, 3=5f(x) 3 = 5 f ( x ) + xg ( x ) ⟹ g ( x ) = 0 , 3 = 5 f ( x ) f ( x ) ∈ Z [ x ] f(x) \in \Z[x] f ( x ) ∈ Z [ x ]

Proposition 2.4.14: Irreducible element generates maximal ideal

∢ P ∈ R P I D p ∈ P ∖ { 0 } ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) ⟺ p ∈ P − \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {PID}} \\

& p \in P \setminus \{0\}

\\

\hline

\\

&\lang p \rang_I \in \mathfrak M_I(P) \iff p \in P^{-}

\end{align*} ∢ P ∈ R P I D p ∈ P ∖ { 0 } ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) ⟺ p ∈ P − Proof

⟹ \implies ⟹

We want to prove that p = u v ⟹ ( u ∈ P ∗ ) ∨ ( v ∈ P ∗ ) p = uv \implies (u \in P^*)\vee(v \in P^*) p = uv ⟹ ( u ∈ P ∗ ) ∨ ( v ∈ P ∗ )

⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) , p = u v ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ u ⟩ I ⟹ ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) { ⟨ p ⟩ I = ⟨ u ⟩ I ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ∃ x ∈ P ∗ : u x = p = u v ⟹ v = x ∈ P ∗ ⟨ u ⟩ I = P ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) u ∈ P ∗ \lang p \rang_I \in \mathfrak M_I(P), p = uv \overset{(2.4.6)}\implies \lang p \rang_I \subseteq \lang u \rang_I \overset{\lang p \rang_I \in \mathfrak M_I(P)}{\implies} \\

\begin{cases}

\lang p \rang_I = \lang u \rang_I \overset{(2.4.6)}\implies \exist x \in P^*: ux = p = uv \implies v = x \in P^*\\

\lang u \rang_I = P \overset{(2.4.6)}\implies u \in P^*

\end{cases} \\

⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) , p = uv ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ u ⟩ I ⟹ ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) ⎩ ⎨ ⎧ ⟨ p ⟩ I = ⟨ u ⟩ I ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ∃ x ∈ P ∗ : ux = p = uv ⟹ v = x ∈ P ∗ ⟨ u ⟩ I = P ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) u ∈ P ∗ ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

We want to prove that ∀ a ∈ P : ⟨ p ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ P ⟹ ( ⟨ a ⟩ I = P ) ∨ ( ⟨ p ⟩ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ) \forall a \in P: \lang p \rang_I \subseteq \lang a \rang_I \subseteq P \implies (\lang a \rang_I=P)\vee(\lang p \rang_I=\lang a \rang_I) ∀ a ∈ P : ⟨ p ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ P ⟹ (⟨ a ⟩ I = P ) ∨ (⟨ p ⟩ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I )

∀ a ∈ P : ⟨ p ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ P ⟹ ∃ x ∈ P : p = a x ⟹ p ∈ P − { x ∈ P ∗ ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I a ∈ P ∗ ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ a ⟩ I = P \forall a \in P: \lang p \rang_I \subseteq \lang a \rang_I \subseteq P \implies \exists x \in P: p = ax \overset{p \in P^-}\implies \\

\begin{cases}

x \in P^* \overset{(2.4.6)}\implies \lang p \rang_I = \lang a \rang_I \\

a \in P^* \overset{(2.4.6)}\implies \lang a \rang_I = P

\end{cases} ∀ a ∈ P : ⟨ p ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ P ⟹ ∃ x ∈ P : p = a x ⟹ p ∈ P − ⎩ ⎨ ⎧ x ∈ P ∗ ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I a ∈ P ∗ ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ a ⟩ I = P □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.15: Irreducible = prime

∢ P ∈ R P I D p ∈ P − ⟺ p ∈ P ( P ) \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{PID}}

\\

\hline

\\

&p \in P^{-} \iff &p \in \mathfrak P(P)

\end{align*} ∢ P ∈ R P I D p ∈ P − ⟺ p ∈ P ( P ) Proof

⟹ \implies ⟹

( 2.4.14 ) ⟹ ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) ⟹ ( 2.3.6 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ P I ( P ) ⟹ ( 2.4.1 ) p ∈ P ( P ) (2.4.14) \implies \lang p \rang_I \in\mathfrak M_I(P) \overset{(2.3.6)}{\implies} \lang p \rang_I \in\mathfrak P_I(P) \overset{(2.4.1)}\implies p \in \mathfrak P(P) \\ ( 2.4.14 ) ⟹ ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ M I ( P ) ⟹ ( 2.3.6 ) ⟨ p ⟩ I ∈ P I ( P ) ⟹ ( 2.4.1 ) p ∈ P ( P ) ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

Follows from ( 2.4.7 ) (2.4.7) ( 2.4.7 )

□ \square □

We proved in ( 2.4.12 ) (2.4.12) ( 2.4.12 ) ( 2.4.17 ) (2.4.17) ( 2.4.17 ) ( 2.4.15 ) (2.4.15) ( 2.4.15 ) ( 2.4.12 ) (2.4.12) ( 2.4.12 ) ( 2.4.17 ) (2.4.17) ( 2.4.17 ) ( 2.4.17 ) (2.4.17) ( 2.4.17 ) ( 2.4.15 ) (2.4.15) ( 2.4.15 ) ( 2.4.12 ) (2.4.12) ( 2.4.12 ) ( 2.4.15 ) (2.4.15) ( 2.4.15 )

Proposition 2.4.16: PID is Noetherian

∢ P ∈ R P I D P ∈ R N \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{PID}}\\

\hline

\\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{N}}

\end{align*} ∢ P ∈ R P I D P ∈ R N Proof

Consider chain of ideals I 1 ⊆ I 2 ⊆ … I_1 \subseteq I_2 \subseteq \ldots I 1 ⊆ I 2 ⊆ … I : = ⋃ i I i I:=\bigcup_i I_i I := ⋃ i I i ( 2.4.9 ) (2.4.9) ( 2.4.9 ) I ⊲ R P I \lhd_R P I ⊲ R P

P ∈ R P I D ⟹ ∃ a ∈ P : I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ N ∈ N : a ∈ I N ⟹ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ a ∈ I N I N ⊆ I = ⋃ i I i I ⟹ I N = I ⟹ ∀ n ≥ N : I = I N ⊆ I n ⊆ I ⟹ I n = I N P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{PID}} \implies \exists a \in P: I = \lang a \rang_I \implies \exists N \in \N: a \in I_N \implies \\

I=\lang a \rang_I \overset{a \in I_N}\subseteq I_N \overset{I=\bigcup_i I_i}\subseteq I \implies I_N = I \implies \\

\forall n \ge N: I=I_N \subseteq I_n \subseteq I \implies I_n = I_N P ∈ R P I D ⟹ ∃ a ∈ P : I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ⟹ ∃ N ∈ N : a ∈ I N ⟹ I = ⟨ a ⟩ I ⊆ a ∈ I N I N ⊆ I = ⋃ i I i I ⟹ I N = I ⟹ ∀ n ≥ N : I = I N ⊆ I n ⊆ I ⟹ I n = I N □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.17: PID is UFD

∢ P ∈ R P I D P ∈ R U F D \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{PID}}\\

\hline

\\

&P \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{UFD}}

\end{align*} ∢ P ∈ R P I D P ∈ R U F D Proof

Existence of factorization

Let's prove that ∀ p ∈ P ∖ ( P ∗ ∪ { 0 } ) : ∃ p 1 , … p k ∈ P − : p = p 1 ⋅ … ⋅ p k \forall p \in P \setminus (P^* \cup \{0\}): \exists p_1, \ldots p_k \in P^-: p= p_1\cdot \ldots \cdot p_k ∀ p ∈ P ∖ ( P ∗ ∪ { 0 }) : ∃ p 1 , … p k ∈ P − : p = p 1 ⋅ … ⋅ p k

If p ∈ P − p \in P^- p ∈ P − ∃ p 1 , p 2 ∈ P ∖ ( P ∗ ∪ { 0 } ) : a = p 1 p 2 \exists p_1, p_2 \in P \setminus (P^* \cup \{0\}): a = p_1p_2 ∃ p 1 , p 2 ∈ P ∖ ( P ∗ ∪ { 0 }) : a = p 1 p 2 p 1 p_1 p 1 p 1 = p 11 p 12 p_1=p_{11}p_{12} p 1 = p 11 p 12 p = p 1 … p k p=p_1\ldots p_k p = p 1 … p k p i p_i p i

Now the only question is - why does this process ever terminate? In other words why is k k k p 1 , p 11 , p 112 , … p_1, p_{11}, p_{112}, \ldots p 1 , p 11 , p 112 , … p 1 , p 2 , p 3 , … p_1, p_{2}, p_{3}, \ldots p 1 , p 2 , p 3 , … p i + 1 ∣ p i p_{i+1} \mid p_i p i + 1 ∣ p i ( 2.4.6 ) (2.4.6) ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ p i ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ p i + 1 ⟩ I \lang p_{i} \rang_I \subseteq \lang p_{i+1} \rang_I ⟨ p i ⟩ I ⊆ ⟨ p i + 1 ⟩ I p i + 1 ∣ p i p_{i+1} \mid p_i p i + 1 ∣ p i p i = p i + 1 x p_i = p_{i+1}x p i = p i + 1 x x ∉ P ∗ ∪ { 0 } x \notin P^* \cup \{0\} x ∈ / P ∗ ∪ { 0 } ( 2.4.6 ) (2.4.6) ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ p i ⟩ I = ⟨ p i + 1 ⟩ I \lang p_{i} \rang_I = \lang p_{i+1} \rang_I ⟨ p i ⟩ I = ⟨ p i + 1 ⟩ I ⟨ p i ⟩ I ⊂ ⟨ p i + 1 ⟩ I \lang p_{i} \rang_I \subset \lang p_{i+1} \rang_I ⟨ p i ⟩ I ⊂ ⟨ p i + 1 ⟩ I ⟨ p 1 ⟩ I ⊂ ⟨ p 2 ⟩ I ⊂ … \lang p_{1} \rang_I \subset \lang p_{2} \rang_I \subset \ldots ⟨ p 1 ⟩ I ⊂ ⟨ p 2 ⟩ I ⊂ … P P P ( 2.4.16 ) (2.4.16) ( 2.4.16 )

Uniqueness of factorization

Assume p 1 … p k = q 1 … q s , p i , q i ∈ P − p_1\ldots p_k=q_1\ldots q_s, p_i, q_i \in P^{-} p 1 … p k = q 1 … q s , p i , q i ∈ P − k ≤ s k \le s k ≤ s

p 1 ∈ P − ⟹ ( 2.4.15 ) p 1 ∈ P ( P ) p 1 ∣ q 1 … q s ⟹ ∃ q j : q j = u 1 p 1 p_1 \in P^{-} \overset{(2.4.15)}{\implies} p_1 \in \mathfrak P(P) \\

p_1 \mid q_1\ldots q_s \implies \exists q_j: q_j = u_1p_1 p 1 ∈ P − ⟹ ( 2.4.15 ) p 1 ∈ P ( P ) p 1 ∣ q 1 … q s ⟹ ∃ q j : q j = u 1 p 1 Since q j , p 1 ∈ P − q_j, p_1 \in P^{-} q j , p 1 ∈ P − u 1 ∈ P ∗ u_1 \in P^* u 1 ∈ P ∗ p 1 p_1 p 1 q i q_i q i

p 2 … p k = u 1 q 1 … q s − 1 p_2\ldots p_k=u_1q_1 \ldots q_{s-1} p 2 … p k = u 1 q 1 … q s − 1 Making this process k k k 1 = v q 1 … q s − k 1 = vq_1\ldots q_{s-k} 1 = v q 1 … q s − k q i ∈ P ∗ q_i \in P^* q i ∈ P ∗ q i ∈ P − q_i \in P^- q i ∈ P − k = s k = s k = s p i = u i q j , u i ∈ P ∗ p_i =u_iq_j, u_i \in P^* p i = u i q j , u i ∈ P ∗

□ \square □

Euclidean domains

def: Norm

∢ B ∈ R I D N : B → N ∪ 0 , N ( 0 ) = 0 N − norm \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} \\

&N: B \to \N \cup 0, N(0) = 0

\\

\hline

\\

&N - \text{norm}

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D N : B → N ∪ 0 , N ( 0 ) = 0 N − norm def: Euclidean domain

∢ E ∈ R I D ∃ N − norm : ∀ a , b ∈ E , b ≠ 0 : ∃ q , r ∈ E : a = b q + r , ( r = 0 ) ∨ ( N ( r ) < N ( b ) ) E ∈ R E \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&E \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal{ID}} \\

&\exists N - \text{norm}: \\

&\forall a, b \in E, b \ne 0: \exists q, r \in E: a = bq + r, (r=0) \vee (N(r) < N(b))

\\

\hline

\\

&E \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal E}

\end{align*} ∢ E ∈ R I D ∃ N − norm : ∀ a , b ∈ E , b = 0 : ∃ q , r ∈ E : a = b q + r , ( r = 0 ) ∨ ( N ( r ) < N ( b )) E ∈ R E Example: Euclidean domain

Z \Z Z N ( x ) = ∣ x ∣ N(x)=|x| N ( x ) = ∣ x ∣

Proposition 2.4.18 Euclidean domain is PID

∢ E ∈ R E E ∈ R P I D \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&E \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal E}

\\

\hline

\\

&E \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {PID}}

\end{align*} ∢ E ∈ R E E ∈ R P I D Proof

We'll prove that any ideal is principal. Consider I ⊲ R E I \lhd_R E I ⊲ R E I = { 0 } I = \{0\} I = { 0 } d ∈ I d \in I d ∈ I

Obviously ⟨ d ⟩ I ⊆ I \lang d \rang_I \subseteq I ⟨ d ⟩ I ⊆ I ⟨ d ⟩ I ⊇ I \lang d \rang_I \supseteq I ⟨ d ⟩ I ⊇ I

∀ a ∈ I ⟹ ∃ q , r ∈ E : a = q d + r , ( r = 0 ) ∨ ( N ( r ) < N ( d ) ) r = a − q d ⟹ r ∈ I \forall a \in I \implies \exists q, r \in E: a = qd + r, (r = 0) \vee (N(r) < N(d)) \\

r = a - qd \implies r \in I ∀ a ∈ I ⟹ ∃ q , r ∈ E : a = q d + r , ( r = 0 ) ∨ ( N ( r ) < N ( d )) r = a − q d ⟹ r ∈ I By definition of d : N ( r ) ≥ N ( d ) d: N(r) \ge N(d) d : N ( r ) ≥ N ( d ) r r r r = 0 r=0 r = 0 ∀ a ∈ I ⟹ a = q d ⟹ a ∈ ⟨ d ⟩ I \forall a \in I \implies a =qd \implies a \in \lang d \rang_I ∀ a ∈ I ⟹ a = q d ⟹ a ∈ ⟨ d ⟩ I

□ \square □

Fields

def: Field

∢ F ∈ R C F ∗ = F ∖ { 0 } F ∈ F \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&F \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {C}} \\

&F^*= F \setminus \{0\}

\\

\hline

\\

&F \in \mathcal F

\end{align*} ∢ F ∈ R C F ∗ = F ∖ { 0 } F ∈ F Proposition 2.4.19: Field is a euclidean domain

∢ F ∈ F F ∈ R E \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&F \in \mathcal F

\\

\hline

\\

&F \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {E}}

\end{align*} ∢ F ∈ F F ∈ R E Proof

First, let's prove F ∈ R I D F \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} F ∈ R I D a , b ∈ F ∗ = F ∖ 0 a, b \in F^* = F \setminus 0 a , b ∈ F ∗ = F ∖ 0 a b = 0 ab=0 ab = 0 a − 1 a b = 0 ⟹ b = 1 ⋅ b = 0 a^{-1}ab=0 \implies b=1\cdot b = 0 a − 1 ab = 0 ⟹ b = 1 ⋅ b = 0 b ∈ F ∖ 0 b \in F \setminus 0 b ∈ F ∖ 0 a ⋅ b ≠ 0 a \cdot b \ne 0 a ⋅ b = 0 R ∈ R I D R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} R ∈ R I D

Next, we define ∀ x ∈ F : N ( x ) : = 0 \forall x \in F: N(x):=0 ∀ x ∈ F : N ( x ) := 0 ∀ a , b ∈ F ∖ { 0 } : a = b ⋅ ( b − 1 a ) + r \forall a, b \in F \setminus \{0\}: a = b\cdot (b^{-1}a)+r ∀ a , b ∈ F ∖ { 0 } : a = b ⋅ ( b − 1 a ) + r r = 0 r=0 r = 0

□ \square □

Proposition 2.4.20: Field criterion

∢ A ∈ R C The following are equivalent: A ∈ F I ⊲ R A ⟹ ( I = { 0 } ) ∨ ( I = A ) B ∈ R C ∖ { 0 } , ϕ : A ⇝ R B , ϕ ( 1 ) = 1 ⟹ ker ϕ = { 0 } \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&A \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C}

\\

\hline

\\

&\text{The following are equivalent:}\\

&\begin{align*}

& A \in \mathcal F \tag{a}\\

& I \lhd_R A \implies (I=\{0\})\vee(I=A) \tag{b} \\

& B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \setminus \{0\}, \phi: A \rightsquigarrow_R B, \phi(1)=1 \implies \ker \phi = \{0\} \hspace{1cm} \tag{c}

\end{align*} \\

\end{align*} ∢ A ∈ R C The following are equivalent: A ∈ F I ⊲ R A ⟹ ( I = { 0 }) ∨ ( I = A ) B ∈ R C ∖ { 0 } , ϕ : A ⇝ R B , ϕ ( 1 ) = 1 ⟹ ker ϕ = { 0 } ( a ) ( b ) ( c ) Proof

( a ) ⟹ ( b ) (a) \implies (b) ( a ) ⟹ ( b )

Consider an ideal I ⊲ R A I\lhd_R A I ⊲ R A a ∈ F ∖ { 0 } = F ∗ a \in F \setminus \{0\}=F^* a ∈ F ∖ { 0 } = F ∗ ( 2.4.6 ) (2.4.6) ( 2.4.6 ) I = A I = A I = A

( b ) ⟹ ( c ) (b) \implies (c) ( b ) ⟹ ( c )

ϕ : A ⇝ R B ⟹ ( 2.3.8 ) ker ϕ ⊲ R A ⟹ ( b ) ( ker ϕ = { 0 } ) ∨ ( ker ϕ = A ) ϕ ( 1 ) = 1 ⟹ ker ϕ ≠ A ⟹ ker ϕ = { 0 } \phi: A \rightsquigarrow_R B \overset{(2.3.8)}\implies \ker \phi \lhd_RA \overset{(b)}\implies (\ker \phi = \{0\}) \vee(\ker \phi = A) \\

\phi(1)=1 \implies \ker \phi \ne A \implies \ker \phi = \{0\} ϕ : A ⇝ R B ⟹ ( 2.3.8 ) ker ϕ ⊲ R A ⟹ ( b ) ( ker ϕ = { 0 }) ∨ ( ker ϕ = A ) ϕ ( 1 ) = 1 ⟹ ker ϕ = A ⟹ ker ϕ = { 0 } ( c ) ⟹ ( a ) (c) \implies (a) ( c ) ⟹ ( a )

We will prove that ∀ a ∈ A ∖ A ∗ : a = 0 \forall a \in A \setminus A^*: a = 0 ∀ a ∈ A ∖ A ∗ : a = 0

a ∈ A ∖ A ∗ ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ a ⟩ I ≠ A ⟹ A / ⟨ a ⟩ I ≠ { 0 + A } a \in A \setminus A^* \overset{(2.4.6)}\implies \lang a \rang_I \ne A \implies A / \lang a \rang_I \ne \{0+A\}\\ a ∈ A ∖ A ∗ ⟹ ( 2.4.6 ) ⟨ a ⟩ I = A ⟹ A / ⟨ a ⟩ I = { 0 + A } That means if we assume B : = A / ⟨ a ⟩ I B:=A / \lang a \rang_I B := A / ⟨ a ⟩ I ϕ \phi ϕ ϕ : A ⇝ R A / ⟨ a ⟩ I , x ↦ x + ⟨ a ⟩ I , ϕ ( 1 ) = 1 + ⟨ a ⟩ I \phi: A \rightsquigarrow_R A / \lang a \rang_I, x \mapsto x+\lang a \rang_I, \phi(1) = 1 + \lang a \rang_I ϕ : A ⇝ R A / ⟨ a ⟩ I , x ↦ x + ⟨ a ⟩ I , ϕ ( 1 ) = 1 + ⟨ a ⟩ I ( c ) (c) ( c ) ker ϕ = { 0 } \ker \phi = \{0\} ker ϕ = { 0 } ker ψ = ⟨ a ⟩ I \ker\psi = \lang a \rang_I ker ψ = ⟨ a ⟩ I a = 0 a = 0 a = 0

□ \square □

Proposition 2.4.21: Factor ring by maximal ideal is a field

∢ R ∈ R C I ⊲ R R I ∈ M I ( R ) ⟺ R / I ∈ F \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \\

&I \lhd_R R \\

\hline

\\

&I \in \mathfrak M_I(R) \iff R/I \in \mathcal F

\end{align*} ∢ R ∈ R C I ⊲ R R I ∈ M I ( R ) ⟺ R / I ∈ F Proof

⟹ \implies ⟹

First, R ∈ R C ⟹ ( a + I ) ( b + I ) = a b + I R / I ∈ R C R \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} \overset{(a+I)(b+I)=ab+I}\implies R/I \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal C} R ∈ R C ⟹ ( a + I ) ( b + I ) = ab + I R / I ∈ R C

Fix some a + I ∈ R / I , a ∉ I a+I \in R/I, a \notin I a + I ∈ R / I , a ∈ / I

Consider an ideal J : = ⟨ a ⟩ I + I J:=\lang a \rang_I + I J := ⟨ a ⟩ I + I ( 2.3.4 ) (2.3.4) ( 2.3.4 ) a ∉ I ⟹ I ⊂ J a \notin I \implies I \subset J a ∈ / I ⟹ I ⊂ J I ∈ M I ( R ) I \in \mathfrak M_I(R) I ∈ M I ( R ) J = R J=R J = R

J = R ⟹ 1 ∈ J ⟹ ∃ b ∈ R , i ∈ I : 1 = b a + i ⟹ 1 + I = b a + I = ( b + I ) ( a + I ) = ( a + I ) ( b + I ) ⟹ b + I = ( a + I ) − 1 J=R \implies 1\in J \implies \exists b \in R, i \in I: 1=ba+i \implies \\

1+I = ba+I=(b+I)(a+I) = (a+I)(b+I) \implies \\

b+I = (a+I)^{-1} J = R ⟹ 1 ∈ J ⟹ ∃ b ∈ R , i ∈ I : 1 = ba + i ⟹ 1 + I = ba + I = ( b + I ) ( a + I ) = ( a + I ) ( b + I ) ⟹ b + I = ( a + I ) − 1 ⟸ \impliedby ⟸

R / I ∈ F ⟹ 0 + I , 1 + I ∈ R / I , 0 + I ≠ 1 + I ⟹ I ⊂ R R/I \in \mathcal F \implies 0+I, 1+I \in R/I, 0+I \ne 1+I \implies I \subset R R / I ∈ F ⟹ 0 + I , 1 + I ∈ R / I , 0 + I = 1 + I ⟹ I ⊂ R

Fix some J ⊲ R R , I ⊂ J J \lhd_R R, I \subset J J ⊲ R R , I ⊂ J J = R J=R J = R I ∈ M I ( R ) I \in \mathfrak M_I(R) I ∈ M I ( R )

Take some a ∈ J ∖ I a \in J \setminus I a ∈ J ∖ I b ∈ R : ( b + I ) = ( a + I ) − 1 b \in R: (b+I)=(a+I)^{-1} b ∈ R : ( b + I ) = ( a + I ) − 1

a b + I = ( a + I ) ( b + I ) = 1 + I ⟹ ∃ i ∈ I : a b + i = 1 ab+I = (a+I)(b+I)=1+I \implies \\

\exists i \in I: ab+i = 1 ab + I = ( a + I ) ( b + I ) = 1 + I ⟹ ∃ i ∈ I : ab + i = 1 Now note that a ∈ J ⟹ a b ∈ J a \in J \implies ab \in J a ∈ J ⟹ ab ∈ J i ∈ I ⟹ i ∈ J i \in I \implies i \in J i ∈ I ⟹ i ∈ J 1 ∈ J 1 \in J 1 ∈ J J = R J = R J = R

□ \square □

def: Fractions equivalence relation

∢ ∼ F : ( a , b ) ∼ F ( c , d ) ⟺ a d = b c ∼ F − fractions equivalence relation a b − equivalence class \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&\sim_F: (a, b) \sim_F (c, d) \iff ad = bc\\

\hline

\\

&\sim_F - \text{fractions equivalence relation} \\

&\frac{a}{b} - \text{equivalence class}

\end{align*}

∢ ∼ F : ( a , b ) ∼ F ( c , d ) ⟺ a d = b c ∼ F − fractions equivalence relation b a − equivalence class def: Field of fractions

∢ B ∈ R I D F ( B ) : = ( { a b , a , b ∈ B } , + , ⋅ ) a b + c d : = a d + b c b d a b ⋅ c d : = a c b d F ( B ) is a field of fractions over B \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

& \mathfrak F(B) := (\{\frac{a}{b}, a, b \in B\}, +, \cdot )\\

&\frac{a}{b} + \frac{c}{d}:= \frac{ad + bc}{bd} \\

&\frac{a}{b} \cdot \frac{c}{d}:=\frac{ac}{bd} \\

\hline

\\

&\mathfrak F(B) \text{ is a field of fractions over } B\\

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D F ( B ) := ({ b a , a , b ∈ B } , + , ⋅ ) b a + d c := b d a d + b c b a ⋅ d c := b d a c F ( B ) is a field of fractions over B In other words, F ( B ) \mathfrak F(B) F ( B ) a / b a/b a / b Q \mathbb Q Q Z \Z Z

Proposition 2.4.22: Field of fractions is a field

∢ B ∈ R I D F ( B ) ∈ F \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

\hline

\\

&\mathfrak F(B) \in \mathcal F

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D F ( B ) ∈ F Proof

First, let's prove that operations on F ( B ) \mathfrak F(B) F ( B ) ( a 1 , b 1 ) ∼ F ( a 2 , b 2 ) , ( c 1 , d 1 ) ∼ F ( c 2 , d 2 ) (a_1, b_1) \sim_F (a_2, b_2), (c_1, d_1) \sim_F (c_2, d_2) ( a 1 , b 1 ) ∼ F ( a 2 , b 2 ) , ( c 1 , d 1 ) ∼ F ( c 2 , d 2 ) a 1 b 2 = a 2 b 1 , c 1 d 2 = c 2 d 1 a_1b_2 = a_2b_1, c_1d_2 = c_2d_1 a 1 b 2 = a 2 b 1 , c 1 d 2 = c 2 d 1

( a 1 d 1 + b 1 c 1 ) ( b 2 d 2 ) = a 1 d 1 b 2 d 2 + b 1 c 1 b 2 d 2 = a 2 d 1 b 1 d 2 + b 1 c 2 b 2 d 1 = = ( a 2 d 2 + c 2 b 2 ) b 1 d 1 ⟹ ( a 1 d 1 + b 1 c 1 , b 1 d 1 ) ∼ F ( a 2 d 2 + b 2 c 2 , b 2 d 2 ) (a_1d_1+b_1c_1)(b_2d_2)=a_1d_1b_2d_2+b_1c_1b_2d_2=a_2d_1b_1d_2+b_1c_2b_2d_1= \\

=(a_2d_2+c_2b_2)b_1d_1 \implies (a_1d_1+b_1c_1, b_1d_1) \sim_F (a_2d_2+b_2c_2, b_2d_2) ( a 1 d 1 + b 1 c 1 ) ( b 2 d 2 ) = a 1 d 1 b 2 d 2 + b 1 c 1 b 2 d 2 = a 2 d 1 b 1 d 2 + b 1 c 2 b 2 d 1 = = ( a 2 d 2 + c 2 b 2 ) b 1 d 1 ⟹ ( a 1 d 1 + b 1 c 1 , b 1 d 1 ) ∼ F ( a 2 d 2 + b 2 c 2 , b 2 d 2 ) a 1 c 1 b 2 d 2 = a 2 c 2 b 1 d 1 ⟹ ( a 1 c 1 , b 1 d 1 ) ∼ F ( a 2 c 2 , b 2 d 2 ) a_1c_1b_2d_2=a_2 c_2b_1d_1 \implies (a_1c_1, b_1d_1) \sim_F (a_2c_2, b_2d_2) a 1 c 1 b 2 d 2 = a 2 c 2 b 1 d 1 ⟹ ( a 1 c 1 , b 1 d 1 ) ∼ F ( a 2 c 2 , b 2 d 2 ) It's easy to prove that operations + + + ⋅ \cdot ⋅ Q \mathbb Q Q

Let's check zero, identity and inverses. 0 : = 0 1 , 1 : = 1 1 , ( a b ) − 1 = b a 0: = \frac{0}{1}, 1:=\frac{1}{1}, (\frac{a}{b})^{-1} = \frac{b}{a} 0 := 1 0 , 1 := 1 1 , ( b a ) − 1 = a b

0 + a b = 0 1 + a b = a ⋅ 1 + 0 ⋅ b b ⋅ 1 = a b 1 ⋅ a b = 1 ⋅ a 1 ⋅ b = a b a b ⋅ b a = a b a b = 1 1 = 1 0+\frac{a}{b} = \frac{0}{1}+\frac{a}{b} = \frac{a\cdot 1 + 0 \cdot b}{ b \cdot 1}= \frac{a}{b} \\

\,

\\

1 \cdot \frac{a}{b} = \frac{1\cdot a}{ 1 \cdot b} = \frac{a}{b} \\

\,

\\

\frac{a}{b}\cdot \frac{b}{a} = \frac{ab}{ab}=\frac{1}{1} =1 0 + b a = 1 0 + b a = b ⋅ 1 a ⋅ 1 + 0 ⋅ b = b a 1 ⋅ b a = 1 ⋅ b 1 ⋅ a = b a b a ⋅ a b = ab ab = 1 1 = 1 □ \square □

Proposition 2.4.23: Field of fractions is a minimal field

∢ B ∈ R I D E ∈ F : B ⊆ R E ∃ ϕ : F ( B ) ⇝ 1 − 1 R E : ∀ a ∈ B : ϕ ( a 1 ) = a \begin{align*}

&\sphericalangle \\

&B \in \mathcal R^{\mathcal {ID}} \\

&E \in \mathcal F: B \subseteq_R E \\

\hline

\\

&\exists\phi:\mathfrak F(B) \overset{1-1}{\rightsquigarrow}_R E: \forall a \in B: \phi(\frac{a}{1})=a

\end{align*} ∢ B ∈ R I D E ∈ F : B ⊆ R E ∃ ϕ : F ( B ) ⇝ 1 − 1 R E : ∀ a ∈ B : ϕ ( 1 a ) = a Proof

Define ϕ : a b ↦ a b − 1 \phi: \frac{a}{b} \mapsto ab^{-1} ϕ : b a ↦ a b − 1

( a , b ) ∼ F ( c , d ) ⟹ a d = b c ⟹ a b − 1 = c d − 1 (a, b) \sim_F (c, d) \implies ad = bc \implies ab^{-1}=cd^{-1} ( a , b ) ∼ F ( c , d ) ⟹ a d = b c ⟹ a b − 1 = c d − 1 Next, let's prove that ϕ \phi ϕ

ϕ ( a b + c d ) = ϕ ( a d + b c b d ) = ( a d + b c ) ⋅ ( b d ) − 1 = a b − 1 + c d − 1 = ϕ ( a b ) + ϕ ( c d ) ϕ ( a b ⋅ c d ) = ϕ ( a c b d ) = a c ( b d ) − 1 = a b − 1 c d − 1 = ϕ ( a b ) ⋅ ϕ ( c d ) \phi(\frac{a}{b} + \frac{c}{d})=\phi(\frac{ad+bc}{bd})=(ad+bc) \cdot (bd)^{-1}=\\

ab^{-1}+cd^{-1}=\phi(\frac{a}{b}) + \phi(\frac{c}{d}) \\

\phi(\frac{a}{b} \cdot \frac{c}{d}) = \phi(\frac{ac}{bd}) = ac(bd)^{-1} = ab^{-1}cd^{-1}=\phi(\frac{a}{b})\cdot\phi(\frac{c}{d}) ϕ ( b a + d c ) = ϕ ( b d a d + b c ) = ( a d + b c ) ⋅ ( b d ) − 1 = a b − 1 + c d − 1 = ϕ ( b a ) + ϕ ( d c ) ϕ ( b a ⋅ d c ) = ϕ ( b d a c ) = a c ( b d ) − 1 = a b − 1 c d − 1 = ϕ ( b a ) ⋅ ϕ ( d c ) Obviously ϕ ( 1 1 ) = 1 \phi(\frac{1}{1})=1 ϕ ( 1 1 ) = 1 ( 2.4.20 ) : ker ϕ = { 0 } ⟹ ϕ : F ( B ) ⇝ 1 − 1 R E (2.4.20): \ker \phi = \{0\} \implies \phi:\mathfrak F(B) \overset{1-1}{\rightsquigarrow}_R E ( 2.4.20 ) : ker ϕ = { 0 } ⟹ ϕ : F ( B ) ⇝ 1 − 1 R E

□ \square □